This post is about a particular style of curtain valance, which originated in the early part of the 19th century and which I have really grown to appreciate and wish was used more often.

The historical example I have come to know well is in the Drawing room of

Newbridge House, Ireland. Since I started work with Alec Cobbe in 1994, I have had the pleasure of numerous visits, as it was built for his direct ancestor Charles Cobbe (1686 - 1765), Archbishop of Dublin.

The house was built in the years around 1750, after plans supplied by no-one

less than James Gibbs and it is this original house that can still today be seen across the

lawn, virtually unchanged. It is a restrained Palladian

structure with 6 windows across the facade; it is three rooms wide

and two rooms deep.

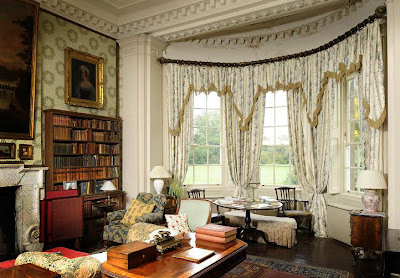

The second generation Cobbes needed more space and in 1764 a new wing was added to the back of the house containing bedrooms above and a very grand drawing room below, which also served as gallery for the growing collection of paintings. One side of the room has a large three-window bay in the middle with single windows on either side. Above these there are heavy gilded poles with enormous wooden rings and from these hang the valances.

It is this arrangement that I have come to like so much. It is actually a really simple way to make a grand statement. There are no swags, tails or cornices and no complicated separate pieces pretending to be one drapery. It is simply a pleated skirt hanging straight down from a decorative pole. Behind this the curtains themselves hang from an invisible track. Unlike 'swag and tail' pelmets with gilded cornices etc both the curtains and valances can easily be removed for cleaning and dusting.

Not only the curtains, but the whole room is an incredible survival, virtually untouched since the 1830s. The flock wallpaper may even date from the 18th century, although a Greek style border was added to it later. The accounts have a

substantial sums to a carver gilder, ‘Mr Kearney’for

curtain ‘rods’ and an upholstering establishment, ‘Messrs Mack and Gibton’ for

‘curtains’ in 1828, which probably refer to these poles and curtains.

The fitted carpet was definitely supplied in 1823 and amazingly is still there.

This is one of the side windows. Curtain geeks like me will want to know that the valance is not 'gathered' but kind of pleated, forming ca 15cm (6") wide folds, and there are small rosettes marking the points where the rings are attached.

A gold coloured braid goes round all 3 sides of the curtains, not just the leading edge and the bottom, as is usual today.

The curtains are remarkably narrow. The track runs along the top of the window architrave and is 160 cm (63") long, but each curtain is 120 cm (47") wide, making for a fullness of only 1.5 (as opposed to the 2.5 - 3 that is often used nowadays). Perhaps not wide, they were certainly long; in fact no less that 30 cm (12") 'overlong'. This extra length was recommended at the time against drafts. When opened, the curtains were hooked up on brass stays, creating great billowing swags.

In 1840, an amateur drawing of the room was done, probably by the young Frances

Power Cobbe (who became an interesting person in her own right), which depicts not only the curtains, but also many pieces of

furniture that are still present in the room today. Interestingly it shows a summer arrangement with four curtains removed, or perhaps pairs of curtains were drawn to one side .

This particular curtain/valance type seems to have been a kind of house style for Newbridge. Above the Drawing Room there was a bedroom with the same bay window and a photograph of ca 1905 shows this room with a continuous skirt, which came down to chair rail height in between the windows. The Dining Room has this type of valance as well, but those came from another house in Co. Dublin, Kenure Park (built in the

18th century and enlarged in the first half of the 19th) and were purchased by the Cobbes when the contents were

sold up in 1964. Finally, the Library has a bay window too, with one big

continuous pole above it. Originally there were two sets of curtains for this room: chintz for summer and heavy rep for

winter. About ten years ago I made new chintz curtains and a valance for the room, in the same style

This style of curtain valance - a skirt hanging straight down from rings on a decorative pole - I haven't found anywhere before the second quarter of the 19th century. It was in that period that books began to be published that not only supplied professional upholsterers but also interested amateurs and house holders with the latest trends and fashions in interior design. One such book, by John Claudius Loudon, contained this plate in 1833, which included a section of the pole/board/track construction, explaining how it worked.

Loudon recommended that this design "may be considered for a cottage finished in the Grecian style , including under that term the Italian manner". What that last bit means I don't know, but it is clear that he thought this style suitable for a room considerably more modest than the Newbridge Drawing Room. He also stated that "the pole to which the drapery is attached would look remarkably well if stained of a mahogany colour, or in a gothic cottage to resemble oak". Perhaps this 'cottage' use, explains why so few valances of this type seem to have survived and how seldom they have been depicted.

Here is one from 1835, decorated with rope on the valance and braid around the curtains:

Valances like this are surprisingly rare in historic interior views; I have only found a handful; amongst them is this country library, with points that come down to about two thirds of the total height.

George Pyne painted a number of student rooms in Oxford colleges around 1860.

They are charming and one day I should write a piece about them here.

Some of them have what I now call the 'Newbridge' type valance:

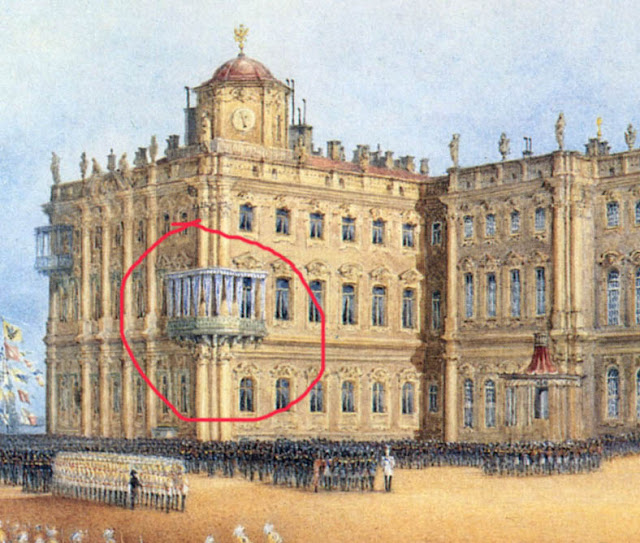

In Germany there was a strong tradition for windows draped in the Empire style throughout the first half of the 19th century, often entirely made of muslin, but around 1850 in the Royal Palace in Berlin there were several rooms with simple, straight valances hung from poles. One of these is just visible in the left margin of my blog - and here is another, in one of those beautiful watercolours by Eduard Gaertner. The fabric in the valance seems to hang almost flat, which is a surprisingly un-grand effect for what must have been an important royal palace.

From the 1870s onwards there was a change in the fashion for curtains and valances, partly caused by writings by authors such as Charles Eastlake, who despised the complicated constructions of fixed swags and tails that were impossible to clean and were deemed ugly and unhealthy dust traps. There were also new theories about fresh air etc and general good health.

Eastlake recommended simple iron rods with curtains that hang straight down, just touching the

floor. Tiebacks were not allowed. The only possible elaboration was a 'lambrequin' ; a rectangular piece of fabric attached to a wooden board above the rod, with the sole function of draft exclusion. His book became extremely influential and the new theories permeated the highest echelons of society. Although rooms could become ever more covered in pattern and crammed with furniture and objects, and although the textiles became ever more richly woven and embroidered, the actual shape of curtains became very simple indeed.

So there was a simplifcation in style but at the same time an elaboration in materials, and this can be clearly observed in the pages of 'Artistic Houses', which was published in 1883 and recorded the latest and most sumptuous interiors of the time in places like New York, Boston and Philadelphia etc. It is a fascinating insight of how the richest people in the world lived at one time, and a must for enthusiasts for Edith Wharton, who was 22 when the book was published and knew some of the houses.

Amongst the 203 photographs only one shows swagged curtains in the style that Eastlake railed against (Mrs Cornelia's M. Stewart's bedroom, but her vast house really belongs to an earlier age).

All other curtains are made from richly embroidered and decorated materials, often with horizontal bands of decoration, and although they look undoubtedly expensive, their construction couldn't be more simple. There is only one exception; the Dining Room of the Clara Jessup Moore House in Philadelphia. Although the window curtains are as simple as Eastlake would have them, over a doorway we find our old friend the valance from a pole:

In the Netherlands there is a beautifully preserved house of the same period, built by a wealthy

Bisdom van Vliet heiress and her husband in ca 1875. She was widowed 6 years later, was childless and left the house and everything in it to a foundation after her death in 1923. It is one of the most complete survivals of late 19th century interiors, as it was only ever lived in by one person.

The interiors show the mid-19th century neo 'tous les Louis' style with swagged and tailed curtain valances everywhere. Everywhere except in the 'front' and 'back' rooms downstairs.

Here the curtains must have been redone about 10 to 20 years later with flat valances hung from brass poles. In the front room these are of red velvet with panels of brocade in the 'artistic' style of the 1880s :

In the back room they are embroidered with flowers in Art Nouveau style, which I would say date from a few years later again. Eastlake would have approved of the fabric and the flat valance, but hanging it from a pole would for him defy the purpose of draft excluder:

Something not dissimilar, called 'Window Lambrequin' was offered in a Boston catalogue of 1883 :

I will end with a couple of windows that were dressed in this 'Newbridge' style more recently, returning first to the original ones, as Alec and I had them copied for English Heritage about ten years ago. When they asked us to redecorate the four main rooms of Kenwood House, London, for various reasons the 1828

of the Newbridge curtains date was exactly right for the dining room, which

doubled as a picture gallery, and we installed exact copies of them.

I also found this American dining room online, decorated (I believe) by Jed Johnson.

This is how it can look in a sleek modern room, although to my mind the poles could have been more interesting :

And finally the curtains I wake up with every day myself, done in a Braquenie fabric which is now sadly discontinued, on a wall of Farrow and Ball 'Dead Salmon'. There is 50 cm (20") of wall between the top of the window and the ceiling cornice, so the valance simply fills that whole space and takes no light away from the room. Putting the pole right up gives the room a great sense of height as well. I think this is a type of curtain valance that is very historical,

very attractive, very simple to make and surprisingly unusual.

Illustrations:

1. Newbridge Front - from Country Life Magazine, Photographer Paul Barker.

3. Newbridge Side window - my photo.

4. Drawing by FP Cobbe - supplied by Alec Cobbe.

6. Curtain design by John Claudius Loudon, from Encyclopedia of Cottage, Farm, and Villa Architecture and Furniture, 1833. In : Capricious Fancy Draping and Curtaining the Historic Interior 1800 - 1930, Gail Caskey Winkler, Philadelphia, 2013.

7. Curtain design by Thomas King, from Valances and Draperies, consisting of New Designs for Fashionable Upholstery, 1835. In : Capricious Fancy Draping and Curtaining the Historic Interior 1800 - 1930, Gail Caskey Winkler, Philadelphia, 2013.

8. Interior of a Library. In: Inside Out, Charles Plante Fine Arts. Also in: Nineteenth-Century Decoration, the Art of the Interior, Charlotte Gere, 1989.

9. Interior of an Oxford College, George Pyne, ca 1856. From Sotheby's sale catalogue (Safra Collection).

10. Room in the Berlin Stadtschloss, by Eduard Gaertner. In: Authentic Decor, The Domestic Interior 1620 - 1920, Peter Thornton, 1984.

11. Dining Room of the Clara Jessup Moore House in Philadelphia. In: The Opulent Interiors of the Gilded Age, all 203 Photographs from 'Artistic Houses', Dover Publications, 1987.

12 & 13. Interiors of Museum Bisdom van Vliet - my photos.

14. Window Lambrequin, from sale catalogue R.H. White & Co. spring and summer 1883. In : Capricious Fancy Draping and Curtaining the Historic Interior 1800 - 1930, Gail Caskey Winkler, Philadelphia, 2013.

15. Kenwood House Dining Room, in: Country Life Magazine

16. Dining Room, Jed Johnson, from Internet.

17. Sitting Room, from Internet

18. Bedroom, my photo.